The conviction of Yadav, along with other politicians and high ranking officials, in separate cases comes at a crucial juncture. That the gap between publicly held beliefs and judicially attested convictions is narrowing, is a healthy sign for democracy.

In one of the most eagerly awaited verdicts that will have significant implications for the politics for the country in general, and that of Bihar in particular, a CBI designated court of Judge PK Singh held Lalu Prasad Yadav guilty in a fodder scam case.

Popularly known as ‘Chara Ghotala’, the case pertains to fraudulent withdrawal of INR 37.7 crore from Chaibasa (then in Bihar, now in Jharkhand) Treasury in the 1990s. The scam was perpetrated over several years, and many Bihar state government administrative and elected officials were involved in it.

Besides the RJD chief 44 other persons – including six politicians and four IAS officers – were also found guilty in one of the five fodder scam cases. Other prominent convicted politicians include former Bihar Chief Minister Jagannath Mishra and JD(U) MP Jagdish Sharma.

A lawyer announced that the quantum of punishment will be announced on October 3 and is set to be more than 4 years.

The case unravels

The fodder scam came to light in Bihar in 1996 when Lalu Prasad was the Chief Minister of the state. Apart from the charges of siphoning of funds, there are also allegations that the accused were involved in the fabrication of “vast herds of fictitious livestock” for which fodder, medicines and animal husbandry equipment was supposedly procured.

Notwithstanding his gimmicks for which Mr. Yadav is (in)famous, he had to resign from the post of CM in 1997 after a court issued an arrest warrant against him in connection with one of the cases.

The FIR was lodged by Bihar government in February 1996 but the case was transferred to CBI a month later. CBI investigated the scam for a year and the charge sheet was filed in 1997. The charges were framed in 2000 following which the Special CBI court commenced trial against Lalu Yadav and 44 other accused.

In an interesting turn of events, Yadav had moved the Jharkhand High Court and later the Supreme Court, seeking change of the judge in the case. Yadav had in his petition alleged that trial court judge PK Singh was biased against him as he is a relative of PK Shahi, Education Minister in the Nitish Kumar Government in Bihar, “who is his (Yadav”s) biggest political enemy”.

RJD’s plea had faced stiff opposition from JD-U leader Rajiv Ranjan who submitted that it would be a ‘travesty of justice’ if the judge is transferred at the far end of the trial. He raised a question on RJD supremo’s petition seeking transfer of the judge who has been hearing the case since 2011.

Both the courts dismissed his petition, and directed him to complete argument in the case before the CBI court.

The Timing

What is so special that makes this case so noteworthy? Are we not witnessing a period of frequent arrests and convictions of politicians – Suresh Kalmadi, Madhu Koda, A Raja, Om Prakash chautala – to name only a few? Some of these have been convicted and others are most likely to be. The sums involved with these gentlemen range from a few hundred crores to lakhs of crores. So why this excitement with a case that dates back to 17 years and involves ‘small’ sum of 37 crores? The biggest differentiator in this case is the timing of the verdict.

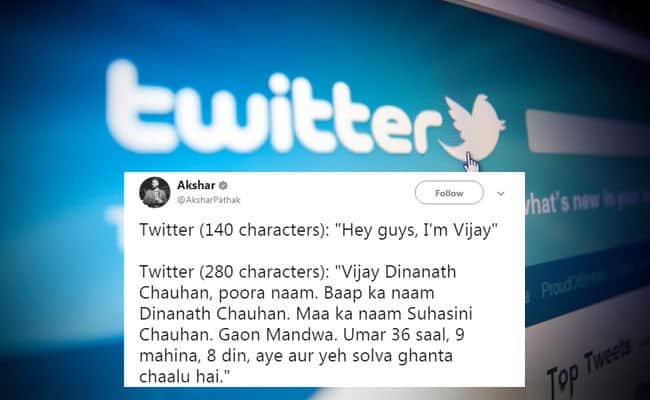

The conviction of Mr. Yadav comes at a time when India’s political history is witnessing significant – if not paradigmatic – shifts. It was only a few weeks ago that the Supreme Court ruled that legislators, if convicted, stand to lose their seats from the very day they are convicted. They no longer get the grace period of three months for appealing that they enjoyed earlier.

Though political calculations of the UPA government tried to get this negated through an ordinance that was almost through, Rahul Baba appeared from nowhere and decreed that the ordinance was fit only to be torn. Lalu’s luck could not have been worse.

New Twist for Electoral Calculations

We are due for elections to five state assemblies, as well as for the Lok Sabha within a year. With Lalu wielding substantial weight in Bihar (that sends 40 MPs to the Lok Sabha) and among the Muslim-Yadav and OBC communities in the northern Indian belt, he was going to be a key figure in the Congress’ strategy to take on Narendra Modi.

It was widely perceived that the ordinance to negate the SC order was primarily aimed at rescuing Lalu. His conviction alters the electoral calculations substantially. While the BJP, with its cry of Swaraj, stands to gain, the Congress and its allies have to do some thinking now.

Secondly, this has significant implications for Bihar politics as well which, in turn will have its own effect at the national level. This will strengthen, though ironically, both the JD(U) as well as the BJP.

However, Nitish Kumar stands to gain more for his frontal attack on corruption and his emphasis on good governance. It also gives us enough reasons to guess that, especially in the light of Rahul Gandhi’s stance on the ordinance, the Congress and JD (U) can move closer.

Yadav’s conviction will badly hit his own party – the RJD – not least because there has never been a succession planning in that party. One silent beneficiary can be Ramvilas Paswan who is also a leader of the backward castes, and can be expected to gain at the cost of the RJD.

Healthy Signs for Democracy

The conviction of Yadav, along with other politicians and high ranking officials, in separate cases comes at a crucial juncture. Justice – procedural as well as substantive – is one of the key pillars on which democracy rests.

The elected representatives are the drivers of parliamentary democracy. The perception – which is becoming a general conviction – that political leaders can get away with almost anything – acts like a termite that undermines peoples’ faith in democracy and its manifest institutions.

That the gap between publicly held beliefs and judicially attested convictions is narrowing, is a healthy sign for democracy. This sign, when seen against the backdrop of the anti-corruption wave, demand for better governance, safety for women, legislations for socio-economic justice etc., is enough to give us hope that the democratic project has affirmed its roots in India, finally.

(Amulya is a writer based in Delhi. He writes on political, socio-economic and developmental issues.)